Chesters Roman Fort is perhaps the best-preserved Roman cavalry fort in Britain. The fort was built in the early 2nd century to guard the point where Hadrian's Wall crossed the River South Tyne. The remains are quite extensive, which makes it very easy to get a feel for the layout of many of the major buildings in the fort. There is an extensive museum showcasing major finds from the site.

History

The fort was begun in AD 124, during the first phase of construction on Hadrian's Wall. Initial plans for the Wall did not include any forts, but within two years plans were changed, to create 15 forts along the course of the wall, manned by auxiliary troops, drawn from legions whose members were not Roman citizens.

The earliest forts were built astride the wall, half extending north and half to the south. At Chesters this involved pulling down a recently built turret and filling in the defensive ditch north of the Wall to make space for building the fort.

Chesters was called Cilurnum by the Romans and was garrisoned by 500 cavalrymen. An inscription on an altar found at Chesters describes the legion as 'ala Augusta ob virtutem appellata', which translates loosely as 'the cavalry regiment known as Augusta for its valour'.

To support the 500 men and their horses the fort required 16 barracks blocks, each housing 32 men and their steeds.

The fort may have been briefly abandoned later in the 2nd century when Roman legions pressed north into Scotland, but we know that the 6th Legion carried out building work in the middle of the 2nd century.

Around AD 160, the 1st Cohort of Vangiones, from the Rhineland, were stationed at Chesters, as evidenced by a touching memorial erected by the cohort's commander to his daughter.

From AD 178 the 2nd Asturians, a Spanish cavalry unit, were based at Chesters, and they remained here until the Roman legions departed Britain in the early 5th century. The barracks we see today were built for the Asturian cavalry and date to the late 2nd or early 3rd century.

A civilian settlement, or vicus, grew up outside the fort. This settlement was at its height from AD 180-250, but by the end of the 3rd century it had largely been abandoned.

There is no archaeological evidence for occupation at Chesters beyond the early 4th century, but it seems likely that the Asturians remained until the Romans officially withdrew in AD 410.

The site was abandoned and used as a source of building stone. Hexham Abbey was built with stones robbed from the bridge abutment at Chesters in AD 675.

The Chesters site was purchased in 1796 by Nathaniel Clayton. He levelled the Roman site to create a landscaped garden for his mansion higher up the hill. The entire site might have been lost were it not for Clayton's son John, who inherited the Chesters property in 1832. John Clayton became fascinated by the Roman ruins on his estate, and began to excavate the fort. He created a museum to exhibit his finds from Chesters and elsewhere along Hadrian's Wall.

Clayton was responsible for saving much of Hadrian's Wall, purchasing sections as they became available and saving them for posterity. It is largely due to his efforts that so much of the Wall remains intact today.

What to see:

Among the excavated buildings at Chesters are the regimental temple, hall, and a large commandant's quarters. The most exciting remain is the remarkably complete bathhouse complex by the river. The bath complex was located outside the fort, in a sheltered spot designed to give the soldiers a break from their cramped barracks.

The baths were not used solely by the soldiers; they were communal baths, used by residents of the vicus and the surrounding area. Here soldiers of every rank could meet and mingle with local inhabitants. Gambling was a popular activity for bathers, and an altar to the goddess Fortuna was discovered in the Chesters bathhouse. Gamblers would often pray to Fortuna for luck in the wagers.

Death in the Baths

The Chesters baths were discovered by complete accident. Workmen digging a drain broke through a layer of silt and discovered a large Roman building which they at first thought was a villa. In the southernmost chamber the workmen found 33 skeletons.

No one knows when or why the skeletons were buried in the bathhouse. Was it a case of foul play? Unfortunately, the skeletons have long since disappeared, so the answer will never be known.

A special viewing platform beside the baths looks across the River South Tyne to the Chesters Bridge Abutment, the last remaining evidence of the Roman bridge that carried Hadrian's Wall over the river.

Another interesting find is the main east gate to the fort. This double gateway opened north of Hadrian's Wall, allowing access to the barbarian lands beyond the Wall. You can see sections of the famous Wall were it joins the gatehouse tower.

Another highlight is the Principia, or headquarters building. Within the Principia is a shrine, and set into the earth behind the shrine is a strongroom, where the regimental records, insignia, and the soldier's pay were kept. Other forts along Hadrian's wall use the same idea; put the pay and important documents in a safe place guarded not only by soldiers but by the gods or goddesses to whom the shrine is dedicated.

Visiting

Chesters is well signposted off the B6318 at Chollerford. I've visited Chesters twice, and can highly recommend it. The excavated sections of the fort are extremely well signposted, with plenty of useful information on how the fort functioned and how soldiers lived here.

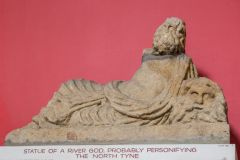

The museum is excellent, with some fascinating finds from Chesters and beyond, including Roman mileposts, altars, and magnificent carvings of gods and goddesses. You can explore the museum using reprints of the original Victorian guide written by John Clayton when he opened the museum to the public in 1896.

About Chesters Roman Fort

Address: Chollerford,

Hadrian's Wall,

Northumberland,

England, NE46 4EU

Attraction Type: Roman Site

Location: Located just West of Chollerford, on the B6318. Paid parking, with fee refunded on entry.

Website: Chesters Roman Fort

English Heritage - see also: English Heritage memberships (official website)

Location

map

OS: NY907701

Photo Credit: David Ross and Britain Express

HERITAGE

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

We've 'tagged' this attraction information to help you find related historic attractions and learn more about major time periods mentioned.

Historic Time Periods:

Find other attractions tagged with:

18th century (Time Period) - 2nd century (Time Period) - 3rd century (Time Period) - 4th century (Time Period) - 5th century (Time Period) - Roman (Time Period) - Victorian (Time Period) -

NEARBY HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS

Heritage Rated from 1- 5 (low to exceptional) on historic interest

Chesters Bridge Abutment (Hadrian's Wall) - 0.4 miles (Roman Site) ![]()

Brunton Turret (Hadrian's Wall) - 0.9 miles (Roman Site) ![]()

Planetrees Roman Wall (Hadrian's Wall) - 1.4 miles (Roman Site) ![]()

Black Carts Turret (Hadrian's Wall) - 1.5 miles (Roman Site) ![]()

Heavenfield, St Oswald's Church - 1.9 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Carrawburgh Temple of Mithras - 3.1 miles (Roman Site) ![]()

Chipchase Castle - 3.9 miles (Historic House) ![]()

Hexham Abbey - 4.1 miles (Historic Church) ![]()

Nearest Holiday Cottages to Chesters Roman Fort:

Humshaugh, Northumberland

Sleeps: 4

Stay from: £295 - 1081

Humshaugh, Northumberland

Sleeps: 4

Stay from: £295 - 1140

More self catering near Chesters Roman Fort