Part 2 of 5

See Part 1 | Part 3| Part 4 | Part 5

Towards the end of his first year, the Prince was summoned along with a group of boys to the Headmaster’s office. Briefed by the Palace beforehand, the Prince knew that he was about to witness one of the most significant moments unfold. The boys were told they would be watching the official closing ceremony of the Empire and Commonwealth Games in Cardiff. In a recorded message to the crowd and television audience, the Queen announced that she intended to mark a “memorable year for the Principality” by creating her son Charles, Prince of Wales. In a statement harking back to mediaeval times, she said: “When he is grown up I will present him to you at Caernarvon.”

After such a momentous event, life continued much as normal at Cheam. Still unsure of himself physically – he did not much enjoy the sporting rigours of public school life – Charles found a channel through which to better express his abilities. Encouraged by one of his masters, he took to the stage, where he was judged competent, “with a good voice and excellent elocution”, and convincingly able to convey the “ambition and bitterness” of his character.

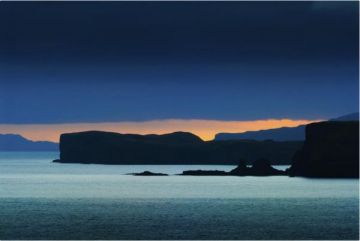

In 1962, after five years, the Prince left Cheam no more enamoured by the place than he was at the age of nine. But if he thought he had endured misery and loneliness there, it was nothing as compared to what awaited him. Following again in the footsteps of his father, Prince Charles proceeded next to Gordonstoun, a school on the north-east coast of Scotland. Still irked by his son's “romantic” nature, the Duke of Edinburgh believed that his old school would benefit the Prince by providing an environment that “would draw him out and develop a little more self-assertiveness in him”. The decision, perhaps well-meaning enough, in fact had quite the opposite effect – condemning the Prince, in his eyes, to little more than a prison sentence.

Even more isolated than at Cheam, the Prince often found himself the target of bullies. On more than one occasion he wrote that the place was “pure hell” and of wishing to return home. He complained of sleepless nights because those sharing his dormitory would take it in turns to throw slippers at him, or hit him with pillows throughout the night. He longed to be back at Balmoral Castle, where he loved to fish, shoot and hunt, or to join his siblings for family parties at Sandringham.

Charles found solace only in the art room, where, under the watchful eye of one of his masters, he turned his hand towards pottery. It was not long before he proved himself adept. While at Gordonstoun, the “action man” son for which his father had so longed also began to appear. He joined the school’s surf-rescue unit and the Coastguard Service, and in his second year he became a crew member of one of the school’s two sailing boats.

After overcoming his dread of exams to gain five Ordinary (O) level passes, the Prince was dispatched next to Timbertop, an outback offshoot of the Geelong Church of England Grammar School in Australia. Here he would learn to develop “initiative and self-reliance”. Though initially cautious, the Prince thoroughly enjoyed his time in Australia. Gone was the homesickness he had felt so acutely at Gordonstoun. In its place was a trace of self-confidence. His return to Scotland in the autumn of 1966 was, as usual, filled with dread, but after his Australian experience he adapted more quickly than previously. The following year, he passed Advanced (A) level exams in History and French, and was finally free to take his leave of the place.

As with so much else in his life, it was decided for him that the Prince should next proceed to university, after which he would pursue a career in the military forces. After much wrangling, Trinity College, Cambridge, was settled upon. The committee summoned to steer his direction had also presumed to decide upon which course of study the Prince would take. When the proposal, which included economics, constitutional law and a modern language, was put to him, the Prince, for the first time, did not hesitate in expressing his disapproval. He wanted, instead, to study Archaeology and Anthropology, which he duly undertook, followed by History in his second year. He was beginning, at last, to exert his own identity.

The Prince’s life at Cambridge was interrupted after four terms by the Government’s wish that he spend some time at a Welsh university prior to his investiture as the Prince of Wales. He was thus enrolled at Aberystwyth University, where his presence was not wholly welcomed either by Welsh nationalists or by academic staff who objected to his “fleeting visit”. Nevertheless, he stayed, and learnt enough of the language to be able to deliver his investiture speech in Welsh.

The investiture took place at the mediaeval castle of Caernarvon on July 1, 1969, when the Prince was aged 20. The ceremony, watched by television audiences worldwide, marked not only his presentation to his constituency, but also his integration into public life. He now had official duties and responsibilities to fulfil, the first of which was a tour of Wales, where, to his apparent surprise, he was met with great warmth and cheer.

After completing his tour of duty, the Prince returned to Cambridge to complete his studies. While there, he became acquainted with a young woman by the name of Camilla Shand. Still somewhat isolated and lonely, the Prince found in Camilla something of a kindred spirit. The affair, however, ended almost before it began, as the Prince was due to begin five years of military service. Soon after his departure, the Prince heard of Camilla’s engagement to Andrew Parker-Bowles. Yet it proved difficult for the Prince to put the matter from his mind.

Over the next five years, Charles was committed to the military forces. Within that time, he graduated from a Sub Lieutenant to Captain of his own ship. Although not the ablest of seamen, he proved himself kind and thoughtful and was known for running a very happy ship. After five years, however, still blighted by homesickness, he was glad to end his service.

His freedom was not without complications, however. Cast ashore at the age of 28 without a job or a clearly defined role, the Prince of Wales’s thoughts, as did those of his family and the nation, turned slowly to marriage.

This is Part 2 of a 5 part profile

Part 1

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Contents copyright 1999-2001 The Royal Report

NOTE: The Royal Report is sadly no longer online.