Julius Caesar

The British Isles first come in contact with the general current of history in the year 55 B.C. In that year Julius Caesar, then engaged in the subjugation of Gaul, thought fit to cross the Channel with a military force, doubtless in the hope of finding that he could add to his resources for the achievement of his personal empire.

He spent only a short time on the island and returned again the next year with larger forces. But he found the prospect less promising than he had anticipated; and having no wish to extend the boundaries of the Roman dominion except as a means to more important ends, he again retired without making any serious attempt at subjugation; and for the next hundred years, the Romans left Britain alone.

The Painted People

But nearly three centuries before Julius Caesar the Greek voyager, Pytheas of Massilia, had visited the British coast and had spoken of its inhabitants by the name of Pretanes, which, according, to the best authorities, is a Celtic term meaning the "painted people," and of this term the later title of Britanni was probably a corruption. There can be no doubt that they were the same race who, at the coming of Julius Caesar, were in the habit of painting or possibly tattooing themselves with woad.

It is generally agreed that the dominant races and languages were Celtic, akin to those of Gaul. Further, it is tolerably clear that there were two or perhaps three waves of Celtic invasion since two Celtic stocks at least can be definitely distinguished. The first, called the Goidelic or Gaelic, found before them non-Aryan races commonly named Iberian, who were partly driven by them into the more inaccessible parts of the islands, and partly absorbed by them.

Brythonic invasion

The second wave is called Brythonic; the Pretanes of Pytheas, and the Britanni of the Romans, who treated their Goidelic kinsmen very much as these had treated the Iberians. In language, at least, there was a very marked distinction between these two waves.

In effect, the Goidels or Gaels were driven into Ireland, the isles, and the highlands of Scotland; while the Brythons occupied England and Wales and the Scottish lowlands. The Gaelic of Scotland and the Erse of Ireland descend from the Goidelic dialect, while the Welsh, the old Cornish, and the Breton tongues descend from the Brythonic.

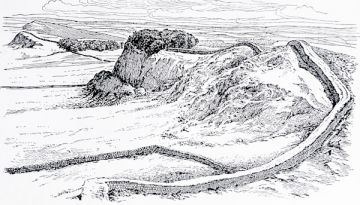

The third wave was also Brythonic in character and seems to have been merely an overflow from the continent of Celts nearly akin to the preceding wave, who occupied. only the southern part of England. When Caesar visited England the last wave represented the highest stage of civilisation so far achieved, while the rest of the Brythons represented a stage intermediate between that of the latest comers and the Gaels. We shall now use the term Briton for the non-Gaelic Celts in general.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age