In 1459, [however], [Queen] Margaret was so palpably preparing for a coup de main, that the Yorkists took up arms, and hostilities were renewed. But although Salisbury won a small victory at Blore Heath, Margaret had succeeded in making it appear that York was the aggressor, whereby much of the support on which he had counted failed him.

When the Royalists advanced against him on an autumn campaign, the Yorkist army melted to pieces and the leaders had to take flight; York himself to Ireland, where he had made himself exÂtremely popular during his lieuÂtenancy, and his eldest son Edward, the young Earl of March, with Salisbury and Warwick, to Calais, of which Warwick was captain. In that capacity the future "kingÂmaker" had latterly achieved a high reputation by his successful operations in the defence of the Channel.

A parliament was called, of what was now to become the usual character. It was simply an asÂsembly of the Royalist nominees; and it opened that sweeping campaign of attainders with which both parties henceforth supplemented their military operations. Instead of bringing persons accused of treason to trial, an Act of parliament was passed by the same process as any other Act of parliament, declaring that a long list of persons were guilty of treason, though the king reserved the right of pardon or mitigation of sentence; a right which on this occasion was freely exercised by the pacific Henry.

Battle of Northampton

But before twelve months had passed, Warwick, who had been concertÂing his plans with Richard in Ireland, landed suddenly on the coast of Kent, where the Yorkist cause was strongly supported. The Royalists had been lulled into a false security; the Yorkists gathered in force, and London admitted him. Thence he marched to Northampton, where the Royalists were hastily gathering, and put them completely to rout, capturing the person of the unlucky king.

At this battle the regular Yorkists' rule was adopted of sparing the commonalty, but giving no quarter to nobles or knights. The battle made Warwick master of the south of England. The north unwisely was left alone. Richard of York returned from Ireland, came, to London where parliament was summoned, and startled and alarmed his supporters by at once asserting his own immediate claim to the throne as the legitimate successor of Richard II.

Warwick and the bulk of Richard's supporters were, however, strongly opposed to this reversal of York's policy. Richard was forced to accept the proposal, to which the captive king gave his consent, that Henry should retain the crown for the rest of his life, but should be succeeded by York, not by the Prince of Wales. The arrangement was ratified by parliament.

Margaret, however, was by no means prepared to accept the exclusion of her son from the succession. She was still at large in Wales, and forthÂwith set about mustering the Lancastrians, as we may now call them, in the north. York at once despatched his son Edward, a lad of eighteen, who had distinguished himself at the battle of Northampton, to the Welsh Marches to keep Wales in check; and leaving Warwick in the south, hurried north himself along with Salisbury.

The Battle of Wakefield

But on the 30th December his small force was overwhelmed at the battle of Wakefield. The Lancastrians gave no quarter. Richard himself, his second son Rutland, and Salisbury, were taken and put to death; several of his principal adherents were slain on the field. The war had degenerated into a vindictive slaughter of rival partisans.

Mortimer's Cross

The victors marching southwards encountered and defeated Warwick in the second battle of St. Albans, some seven weeks after Wakefield, recovered the person of the captive Henry, and advanced to bargain with the Londoners for admission to the capital. But in the meantime the Earl of March had routed a Royalist force at Mortimer's Cross, and was hurrying to join Warwick.

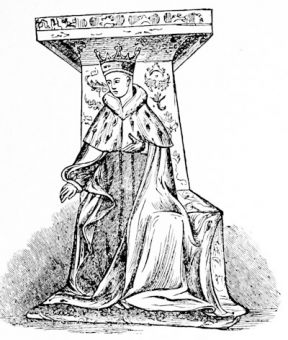

Edward IV crowned

The Yorkist leaders now also hastened to London, but, unlike the Lancastrians, were immediately admitted. The slaughter at Wakefield had removed Warwick's scruples, and, with the acclamations of the Londoners and the troops, Edward IV was proclaimed king on the ground that the parliament of 1399 had had no power to transfer the succession from the legitimate line of the Mortimers.

The Battle of Towton

The foiled Lancastrians retreated to the north; Edward and Warwick were soon in pursuit. A great battle, fought at Towton, was decisive. After a desperate struggle the Lancastrians were utterly routed with tremendous slaughter, and Wakefield was avenged by the death of all prisoners of any position who were taken. King Henry, who had been delivered from the custody of Warwick at the battle of St. Albans, escaped to Scotland with his queen.

The Act of Attainder

Warwick was left to keep the north quiet while Edward returned to London, and was crowned in state. In November the king called his first parliament, of course a purely Yorkist assembly. It passed an Act of Attainder in which there were more than a hundred and thirty names of the living and the dead; the point of these sweeping measures was obviously the confiscation of the estates of the attainted, and their distribution among the adherents of the victorious side. Incidentally, the parliament proÂnounced that the three Henrys had been usurpers, though the benignant Edward was pleased to confirm the charters which the usurpers had granted, and the honours and privileges bestowed by them, except in the case of persons now attainted.

The young king then gave himself up to public displays and private dissipations; content apparently to leave politics and government to the cousin who had made him king. Next year, however, the energetic Margaret of Anjou was again at work, and kept Warwick busy until the summer of 1463, when her followers were dispersed, and she herself only escaped capture by throwing herself, according to a tradiÂtion of good authority, upon the generosity of a robber whom she met in her flight, who conveyed her into safety. A final desperÂate effort of the Lancastrians was crushed in the following year by Warwick's brother, Montague, at Hedgely Moor and Hexham.

France

But a rupture was approaching between the king and his too powerful cousin to explain which we must briefly refer to French affairs since the expulsion of the English. Louis XI was now on the French throne, and was engaged in consolidating the supremacy of the Crown over the feudal nobility, mainly by the methods of intrigue. Philip, Duke of Burgundy, however, having by marriage acquired great possessions in the Low Countries, had virtually made himself an independent monarch, being in effect lord of the Netherlands as well as of the duchy of Burgundy in France, and of the county of Burgundy or Franche Comte, which fell within the German Empire.

Hence though Burgundy was the name generally given inclusively to the whole dominion, Burgundy itself was the less important part of it, the more important, at least from the English point of view, being the Netherlands. Neither Louis nor Philip was willing to see the strength of the other increased.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age