Protector Gloucester

The need for a regency was obvious. The young king was at Ludlow in the hands of the queen mother's brother and son, Rivers and Grey; the young Duke of York was with the queen herself in London, so that the advantages lay with the queen's family for securing the regency to her. But they were unpopular, and Gloucester, who was in the north, knew that he could count upon strong support in securing the regency for himself. In company with the Duke of Buckingham he overtook Edward and his escort on their way to London, and forthwith arrested Rivers and Grey. The queen-mother took sanctuary at Westminster along with the rest of her children, and the council immediately acknowledged Gloucester as Protector.

Hastings executed

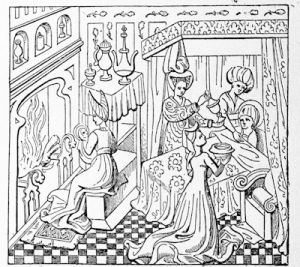

But the sudden death of his brother had suggested to Richard ambitions which went far beyond a mere protectorate. His scheme was to declare the children of Edward IV illegitimate, and to claim the crown for himself. He privately secured the support of some of the great lords who were purchasable, and six weeks after receiving the protectorate he arrested at the Council Board Lord Hastings, a trusted friend of the late king, Bishop Morton, and others from whom he expected opposition. Hastings was beheaded there and then without trial.

The Princes in the Tower

Then he cajoled or frightened the queen into handing over to him the young Duke of York, who was placed in the Tower along with his brother the king; not of course, nominally, as a prisoner. Next his design was revealed when a certain Dr. Shaw preached a sermon at Paul's Cross, in which he affirmed that the late king's marriage with Elizabeth Woodville had been null and void because he was precontracted to another lady.

Richard's Coronation

The congregation received the sermon in amazed silence, but London was practically overawed by the presence of a large number of Gloucester's and Buckingham's retainers; and an assembly which passed for a parliament was induced to petition Gloucester to take upon himself the royal office as the legitimate head of the House of York, in priority to the late king's "bastard" children, and to those of Clarence who were debarred by their father's attainder. After a show of reluctance Gloucester assented, and a few days later was crowned king. The prisoners Rivers and Grey had already been executed. Nearly all the magnates of the realm formally assented by being present at the coronation. Nowhere was there any sign of resistance to the coup d'etat.

The princes disappear

Richard started on a progress through the Midlands. During his absence the two young princes were murdered in the Tower; that is, they disappeared, though their bones were not discovered till nearly two hundred years afterwards. That the boys were murdered no one at the time seems to have doubted at all, though the mystery attending their death was made use of for political purposes in the next reign.

Buckingham's Plot

But the supporters of Richard in his usurpation had not anticipated that it would be sealed by a crime at which all men shuddered. For the most part they were terrorised into silence; one at least was frightened into conspiracy, Buckingham, the representative of the line of the youngest son of King Edward III, while his mother was a Beaufort, entered upon a plot which aimed at uniting the Yorkist and Lancastrian interests by the marriage of the young Earl of Richmond, the head of the Beaufort connection, with Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of Edward IV. But Buckingham's insurrection in the autumn was abortive Premature risings broke it up, and Buckingham himself was caught and beheaded.

Richmond, who had found safety in Brittany since his early boyhood, should have joined the insurrection, and the delay caused by communicating with him was partly responsible for the false start which ensured failure. It was not his fault that when he attempted to cross the Channel be was beaten off by tempests, so that when he managed to reach England it was only to find that he was too late and must hasten back to Brittany. The elements indeed fought against Buckingham; had the cause of Richard been a righteous one, the Duke's overthrow would probably have been attributed to Divine intervention, for his movements had been completely paralysed by terrific rains and floods.

Richard possessed the ability which, under happier circumstances, might have made him a powerful king, held in honour if not in affection by posterity; for like his brilliant brother he had great military and diplomatic ability, and unlike him was an untiring worker, and his administrative skill was well tested. But Edward's numerous progeny barred him from all chance of becoming king except by sheer usurpation; the chance of usurpation presented itself only because the king died suddenly before any of his offspring were of age.

Ten years later, Gloucester would have had no chance at all. The temptation to seize the crown presented itself; he yielded to it. The violence of the methods by which he had paralysed opposition, and the weakness of the plea by which he had procured the setting aside of his nephew, drove him to the murder of the young princes as the only means of securing the crown of which he had robbed them.

He had committed himself hopelessly to the career of the typical tyrant, upon whom ruthless violence is forced as the only alternative to that ruin which. the violence itself not seldom precipitates. The murder of the princes drove Buckingham to revolt; the revolt of Buckingham carried home to Richard that there was not one of his supporters upon whose fidelity he could now count; while among those supporters no man knew when the king's distrust might display itself — whether the caress was merely the prelude to a dagger thrust.

Bill of Attainder

Yet after Buckingham's fall there was a pause. Richard hoped to strengthen himself by combining severity with conciliation. In January he called the only full parliament of his reign. As a matter of course it passed a sweeping Bill of Attainder, not so much in order to penalise enemies as to provide out of the confiscated estates means for purchasing support. The Commons were conciliated by the king's abstention from calling for taxation, by a statutory declaration that benevolences were illegal, and by a measure directed against the corruption and intimidation of juries. The parliament further confirmed the succession of Richard's son, Edward, who had already been made Prince of Wales.

Then this Prince Edward died. There was no prospect of another child being born to the king, who was forced to recognise as his heir-presumptive John de la Pole, whom we shall presently meet as the Earl of Lincoln. If the claim of Clarence's children had been recognised, it would have taken precedence of Richard's own; they were set aside, on the plea of Clarence's attainder. John was the son of the eldest sister of Edward IV and Richard III, who had been married to the Duke of Suffolk.

Henry Tudor

Richard strove successfully to secure his own recognition from most of the continental potentates; but France gave shelter to Richmond and to the fugitives from England who were gathering to his support. Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, was recognised as their head by the Lancastrians, as being the male representative of the house of Beaufort, through his mother, Margaret Beaufort, who had married Edmund Tudor. Edmund's father, Owen Tudor, was a Welsh knight who had married Catherine of France, the widow of Henry V. This had brought the Tudors into some prominence, but did not, of course, affect the succession to the Crown.

Whatever Richard may have gained through his parliament in the way of popular favour was lost in the following year, when he again resorted to illegal and arbitrary methods of obtaining money. Public opinion, too, was further shocked by the rumour that Richard was contemplating a marriage with his own niece, Elizabeth; daughter of Edward IV.

There is some warrant for the belief, in the fact that Richard had abstained, and continued to abstain, from the obvious course of marrying the girl to some nonentity; and when Richard's queen died, it was commonly supposed that he had made away with her in order to facilitate the scandalous design. Richard found himself obliged to declare publicly his innocence of the purpose attriÂbuted to him.

Henry Tudor invades

Through the summer, Henry was preparing for an invasion. In August he succeeded in landing at Milford Haven, being secure of Welsh support in virtue of his own Welsh descent. Richard gathered an army, but many of the lords held aloof altogether, and many of those who assembled with professions of loyalty to him were suspected, with good reason, of treacherÂous intent.

The Battle of Bosworth Field

The armies met at Bosworth Field. Lord Stanley was approachÂing, professedly to support Richard, but actually pledged to Henry. Richard's left wing, led by Northumberland, refused to join battle. Richard, in the centre, made a furious attack; so furious that for a moment there seemed a chance of victory. But only for a moment. Stanley's forces fell upon his flank. The battle was lost, but Richard refused to fly, and fell upon the field, fighting desperately. The crown he had been wearing on his helmet was picked up and set on Richmond's head by Lord Stanley; and on the field of battle the victor was hailed as King Henry VII.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age