The war [of the Austrian Succession] which lasted from 1739 to 1748 was, from a British point of view, singularly futile and unproductive. But out of it arose, while it was still in progress, two episodes of signal importance. One was the last great effort of Jacobitlsm, the failure of which finally freed the country from the constantly lurking spectre of civil war.

The other was the attempt made by the servants of the French East India Company to eject their British rivals, an attempt which presently recoiled upon their own heads, ignominious collapse of the rising of 1715 damped the somewhat lukewarm ardour of English Jacobites.

In Scotland the enthusiasm of loyalty to the Stuarts remained alive among some of the Highland clans, and thrilled the romantic hearts of many ladies. The hope that a Stuart restoration would put an end to the Union with England was cherished north of the Tweed by many who cared nothing for the rights of dynasties.

But the real fervour, the real sanguine belief that "James III and VIII." would yet come by his own, was to be found chiefly among the exiles or the sons of the exiles who had departed from Limerick, or had taken flight after the "Fifteen."

Character of the Pretender

The king whose honest bigotry, combined with an obstinate stupidity, lost him the crown of England, was succeeded by the unfortunate prince who lives in the pages of Thackeray as a voluptuary who threw away a crown to gratify an amour. The real James was a meritorious person who habitually endeavoured to do what he believed to be his duty. He would not sacrifice loyalty to his faith for the sake of a crown, though half England would have turned Jacobite if he had turned Protestant.

He conceived it to be his duty to regain the crown of his fathers, but, not without plenty of excuse, he was a melancholy pessimist, painfully conscious that he was fighting a losing battle. He was free from the conspicuous faults of his father, of his uncle Charles II, and of his son Charles Edward; unhappily his personality was not inspiring but chilling. For that reason he was singularly ill-fitted to undertake the role which fate had thrust upon him.

Jacobite plots

Jacobite plots and intrigues continued with varying activity during the thirty years which followed the "Fifteen." Half the English Tories would perhaps have liked to see a restoration; many Tories and not a few Whigs, while regarding a restoration as a disturbing possibility, were anxious to stand well at the Stuart court if that possibility should materialise; Sanguine exiles were easily persuaded to believe that the Stuart cause was really popular in England, as it in fact was to a large extent in Scotland. Ireland was too powerless to count. But Jacobites in England and Scotland held to a firm conviction that no rising was possible without active military support from beyond the Channel.

The long period of the French alliance made any such hopes futile, at least after Alberoni was dismissed from Spain. Hope revived when Britain was again involved in the War of the Austrian Succession. It was encouraged by France, since the British Government was thereby kept in fear of a Jacobite rising. In 1644, when France and Great Britain openly declared war, an invasion for the avowed purpose of effecting a Jacobite restoration was projected. Saxe himself was to have been in command, but at the chosen hour the transports were wrecked; the moment passed, and the French decided not to divert their arms from the conquest of the Netherlands.

The Young Pretender

But the fiery enthusiasm and the magnetic personality in which James was wanting were present in his son, Charles Edward, who was five-and-twenty years of age when he played for the great stake and lost. Handsome, athletic, generous, endowed in full measure with that personal for which so many members of the Stuart family were conspicuous, we may, after the event, still trace in him warning signs of those weaknesses which, after the great failure, hurried him to moral ruin; yet it may be that they would never have developed if his venture had been crowned with success.

The chance of French help was gone; the prince resolved that at all costs he would strike his blow for the crown. Every trustworthy adherent of his cause warned him that the attempt would be madÂness, that the English JacoÂbites would not rise, that the Highland chiefs themselves would not deliberately thrust their necks into a halter.

In defiance of all advice the prince sailed from France with seven companions, slipped up the west coast, and landed in Moidart, the south-western corner of Inverness-shire, a remote point, beyond the ken of government officials.

Thither he summoned the chiefs in whom he trusted. Some were wise and would not come; they wished the cause well, but objected to a venture for which they saw no remotest prospect of success. Others came, each one bent on dissuading the prince and declaring that he himself would not be beguiled into an act of sheer madness. They might have held out if Donald Cameron of Lochiel had been able to resist the prince's appeal. But Lochiel gave way.

The taking of Edinburgh

If the prince was bent on ruin Lochiel would stand and fall beside him. Lochiel's action turned the scale; chief after chief came in. The news filtered through at last to Sir John Cope, the commander of the government forces. Cope marched into the Highlands, intending to throw himself between Charles and the doubtful clans of the North. Charles slipped past him and marched upon Edinburgh via Perth, while the baffled Cope moved Inverness bring his forces back to Dunbar by sea.

A party of dragoons sent out from Edinburgh to meet the advance but fled in a panic without striking a blow - an exhibition known as the Canter of Colt Brigg. The city of Edinburgh offered no resistance, and in fact welcomed the prince, though the Castle defied him.

While Charles held his court at Holyrood, Cope returned from the North and approached Leith. Guided across an intervening marsh on a night march, the Highlanders fell upon the government troops as the morning mists were breaking and scattered them in a discreditable rout at Prestonpans. Scotland was apparently in the hands of the Jacobites.

Invasion of England

For five weeks Charles delayed, beguiled by hopes of Jacobite rising and of a possible diversion from France. But while he delayed the government in London was recalling troops from the Netherlands. The one chance lay in a dash to the South, in demoralising opposition by sheer audacity.

Charles flung himself across the border at the head of his six thousand Highlanders, evaded first Wade and then Cumberland by sending each of them off on a false scent, and advanced as far as Derby. London was in a state of complete panic, and it was half believed that the approach of Charles would be the signal for the troops which still barred his advance either to join his standard or to run away.

Charles would have dashed on, but less reckless counsels prevailed with the Highland chiefs. No Jacobites had joined them on the march, none had shown signs of rising, no Frenchmen had landed. They were far from their homes; if they advanced the slightest check would involve irretrievable disaster.

In bitterness of spirit Charles yielded, and the army turned its face northward. Perhaps there was one chance in a thousand of success if he had advanced. There was no chance at all when once he had begun to retrace his steps. Eight weeks after the Highland army had started from Edinburgh it was back again at Glasgow (December 26). The shrewd management of Duncan Forbes had kept the rest of the clans quiet.

The Battle of Culloden

In the rearguard skirmishes which took place during the retreat the government troops had come off badly; Charles now laid siege to Stirling, and at Falkirk a complete defeat was inflicted upon General Hawley, who was in command of the pursuing force, Cumberland having been detained in the South, But this was the last success.

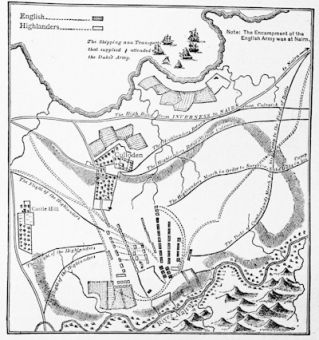

Disagreements and jealousies divided the prince's council, the siege of Stirling was abandoned, and the insurgents retired into the Highlands. Thither they were pursued as the spring came on by Cumberland, who maintained his communications with the coast, where a supporting fleet attended his movements. No fresh clans joined the Stuart standard.

On April 15th the two forces were in close proximity, the government troops well fed and in good condition, while the Highlanders were on very short rations. Cumberland's army was drawn up on Culloden Moor. Charles attempted to effect a surprise by a night march, but the design was spoilt by delays. Nevertheless the cause was staked on a pitched battle.

Under Montrose, under Dundee, under Charles himself, the Highlanders had routed larger bodies of regular troops by the fury of their onset. For this Cumberland prepared, his superior numbers enabling him to draw up his troops in three lines. The rush of the Highlanders broke the first, but their advance was stopped and turned into a rout by the deadly volleys from the second line.

Aftermath of Culloden

Recovery was hopeless. The clans of Culloden were scattered in flight, and Cumberland earned his nickname of the Butcher by the savage brutality displayed on the field and in the consequent penal operations. For after Culloden armed resistance was no longer possible, and the prince himself became a fugitive. The Duke merely scoffed at the pacificatory wisdom of Forbes. What followed was not war, but a hunt for fugitives.

Hairbreadth escapes, splendid deeds of loyalty and devotion, and the glow of romance, give a unique fascination to the story of the Forty-five. As a matter of rational calculation the great adventure was doomed to failure from the very outset, yet chivalry, loyalty, and sheer audacity had actually brought some six thousand clansmen from the wild Highlands of Scotland within measurable distance of winning back the British crown the house of Stuart.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age