William of Orange

William of Orange was primarily a Dutch patriot whose ruling passion was the desire to curb the aggression of Louis XIV. If he wanted the crown of England, which, until the birth of King James's son, had seemed likely to descend to his own wife in the natural course of events, it was not from motives of personal ambition, but because it would secure England as the ally of Holland against France.

As matters stood, while James reigned in England the king, if left to his own devices, was very unlikely to join an anti-French coalition, although English sentiment was notoriously hostile to France. William had no idea of coming forward as the champion of an English party to eject James from his throne and seat himself on it as an obvious usurper.

The defence of Holland against Louis was much more to him than the acquisition of an exceedingly unstable throne which would prevent him from throwing all his energies into European politics. But it would be a very different thing if he reinforced English public opinion so as to enable it to compel James to act as it directed. To do so, however, it was imperative for him to be quite certain that his intervention would be acceptÂable to public opinion, and that the policy he advocated would be endorsed by it.

The birth of the prince gave him a fresh incentive. There was no longer any reason to expect that sooner or later his wife would succeed to the throne without any intervention on his part. Already in spring he had gone so far as to promise that he would intervene in arms if a request that he should do so came from sufficiently influential quarters.

That request had now come, backed by the urgent advice that he should cancel his first formal recognition of the birth of an heir to the throne, and should assert his wife's title to the succession, repudiating the legitimacy of the lately born infant.

Louis XIV, unfortunately for himself, played into the hands of his adversary. In order that William might take active steps in England it was in the first place necessary for him to have an effective force of Dutch troops at his disposal to take part in the enterprise, since it would by no means have satisfied him to depend upon insurrectionary levies in face of the king's troops.

In the second place William could not move if Holland itself were being immediately threatened by Louis; in such circumstances Dutch troops, the Dutch navy, and the Dutch Stadtholder could not absent themselves. In the third place it was desirable to avoid giving the enterprise the appearance of an anti-Catholic crusade lest William's Catholic allies on the continent should be offended.

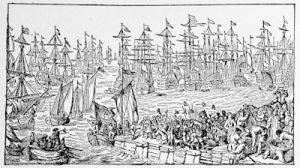

Now Louis, by the great persecution of his own Protestant subjects, had secured the predominance of the anti-French party in Protestant Holland; suspicions of an alliance between James and Louis fostered there the sentiment which favoured William's plan. The Stadtholder found no great difficulty in procuring means for substantial armament, nominally for the defence of Holland.

Again, if Louis had realised what would be the outcome of William's intervention in England, he might have secured himself against future woes by merely keeping the Dutch in fear of invasion. But he grasped at the prospect of an immediate gain instead of warding off the future danger. The office of Archbishop of Cologne, whose holder was one of the seven electoral princes of the Empire, was vacant.

Louis's candidate for the electorship was defeated by the Imperial and Papal candidate, through the action of the Pope, and Louis resolved to enforce his claim at the sword's point. French troops entered the Palatinate. Louis, if the phrase may be permitted, killed two of William's birds for him with one stone. He had in effect made an aggressive attack at once on the two heads, ecclesiastical and secular, of Roman Catholic Christendom, the Pope and the Emperor.

There was no fear that those powers would now quarrel with William for an enterprise to restrain James from associating himself with Louis. And further, by invading the Palatinate, Louis had committed himself to a campaign which. precluded him from making any immediate attack upon Holland, and had thereby set William and the Dutch troops and fleet free for independent action.

No one except Louis and James had any ostensible ground for opposing William's policy. More than twelve months ago, in response to James's attempt to procure his endorsement of the policy of "toleration," he had very expressly made known his own view - that freedom of worship was desirable, but that the religious tests, as conditions of holding public office, ought not to be withdrawn. That satisfied nine-tenths of the people of England, and satisfied also the Catholic Powers.

Meanwhile, for nearly three months after the acquittal of the bishops James continued to blunder along the old line, dismissed the two judges who had been in favour of the bishops, threatened the clergy who had abstained from reading the Declaration of Indulgence, and shut his eyes to William's preparations. Then he took sudden alarm. Troops were hurried over from Ireland and summoned from Scotland.

Royal concessions

Despairing, of vigorous support from the dissenters, the king executed a volte face, and made a series of concessions to the Anglicans. Officials who had been dismissed for adhering to the Test Act were reinstated. And yet although he had announced his intention of summoning a parliament - in which the Commons for reasons already explained, would have been in effect a packed assembly' and the Lords could have been controlled by the creation of peers and the readmission of Roman Catholics—he feared the risks; parliament was not summoned.

This article is excerpted from the book, 'A History of the British Nation', by AD Innes, published in 1912 by TC & EC Jack, London. I picked up this delightful tome at a second-hand bookstore in Calgary, Canada, some years ago. Since it is now more than 70 years since Mr Innes's death in 1938, we are able to share the complete text of this book with Britain Express readers. Some of the author's views may be controversial by modern standards, particularly his attitudes towards other cultures and races, but it is worth reading as a period piece of British attitudes at the time of writing.

History

Prehistory - Roman

Britain - Dark Ages - Medieval

Britain - The Tudor Era - The

Stuarts - Georgian Britain - The Victorian Age